2024/2025 LRO Screening Study Case Studies

Read the Case Studies

- High Flow Water Storage: Hydrological analysis confirms that high-flow water storage is a viable option, with sufficient water available to fill reservoirs. This strategy not only improves water security for local farms but also offers potential downstream flood mitigation and helps maintain environmental flows.

- Expanding Irrigation Reservoirs: The study’s modelling shows that expanding a planned irrigation reservoir from 300,000 m³ to 600,000 m³ would increase irrigation reliability to 90% in dry years and 95% over a 20-year drought cycle.

- Licence Aggregation and Water Rights Sharing: Stakeholder engagement highlighted strong support for water sharing to optimise use across farms. While sharing abstraction licences between the two farms could increase overall water availability by 4-6%, catchment-scale initiatives have the potential to more significantly reduce irrigation deficits, particularly during drought years.

- Effective Water Resilience Solutions: High-flow water storage, expanded irrigation reservoirs, and water sharing are practical strategies to enhance water availability and drought resilience in this area.

- Regulatory Considerations: While regulatory challenges exist, these solutions can be implemented effectively within current guidelines.

- Collaborative Approach: Cooperation between farms, including joint solutions like shared reservoirs and aggregated licences, optimises water management and reduces costs.

- Long-Term Success: Ongoing cooperation and integrated management are essential for sustaining water resilience over time.

- Rainwater Harvesting: Collecting rainwater from glasshouses and polytunnels is a key water source for this grower group. Optimising its use through storage expansion and water sharing can significantly improve water resilience.

- Impact of LROs: The additional water provided by the top three LROs may not fully meet peak demand but will reduce licensing pressure and support more sustainable water sourcing and usage.

- Adapting to Climate Change: Expanding storage capacity and using unlicensed sources like rainwater harvesting will help mitigate drought impacts by allowing water to be carried over between seasons.

- The Importance of Collaboration: Working together is key to making the most of available water. Physical transfers and water rights sharing agreements can improve distribution efficiency across sites, enhancing overall resilience.

On-Farm Storage Reservoirs and High-Flow Abstraction: This LRO involves capturing high winter flows for on-farm storage, addressing both water scarcity and flood risks. Even if there were to be significant reductions to existing licences and in the driest climate change scenario, JBA found that a 100,000 m³ reservoir could sustain adequate supply for the farms involved in the long-term. Ample winter water availability means that high-flow abstractions would reliably fill this reservoir, enhancing water management flexibility and potentially reducing local flooding.

Water Rights Trading and Water Sharing Agreements: This LRO enables the transfer or sharing of underutilised water rights to maximise existing resources. In the lower Upper Roding catchment, average licence utilisation ranged from 0–15% of the allowable annual volume between 1998 and 2024, with four licences entirely unused. This presents an opportunity for upstream farms facing water shortages to access additional resources through trading, optimising allocations in a catchment where new abstraction licences are limited.

Top Solution: Combining storage with floodwater use offers the most reliable way to buffer seasonal variability and secure irrigation.

Regulatory Potential: Refining high-flow abstraction rules could unlock significant water resources, boosting reliability and efficiency.

Stronger Together: Licence trading and water sharing can optimise water use, mobilising underutilised licences to improve access and reduce reliance on new abstractions.

Multi-Benefit Approach: Floodwater reuse and collaborative management strengthen climate resilience while supporting agriculture and biodiversity.

Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) uses natural aquifers for additional water storage. During wet years, surplus water is diverted into recharge lagoons, which gradually drain into the aquifer, raising groundwater levels and stabilising river flows. This nature-based approach aligns with the group's Landscape Recovery Scheme, offering potential synergies. While MAR has long-term potential, its implementation is costly and complex, requiring extensive groundwater modelling and regulatory approval to determine how much water can be recovered.

Outflow Collection redirects part of the lower Nar outflow, near its confluence with the River Great Ouse, to a central reservoir or existing storage sites. By capturing potentially available freshwater, it provides a reliable supply and aligns well with other catchment projects. However, success depends on strong stakeholder collaboration and long-term regulatory support.

Automation improves efficiency by automating pumping switches and enabling high summer flow capture. Faster valve switching, automated EA approvals that reduce lag time, and new summer pumping rules to allow abstraction beyond current licence periods make water use more responsive. While automation offers only a modest improvement in water security, it enhances system efficiency and transparency among stakeholders.

Water Sharing formalises existing informal agreements between farms, redistributing surplus groundwater to reduce reliance on external imports. Given the extensive pipeline infrastructure already in place, this solution is simple and effective, though its overall impact is smaller compared to other options.

MAR, while potentially beneficial long-term, carries high costs and uncertainties around regulatory approval and water yield that may limit its viability.

Outflow collection appears highly promising, balancing feasibility and water supply gains, though it requires strong stakeholder coordination and regulatory backing.

Automation improves efficiency with modest investment but does not significantly enhance water security.

Water sharing presents a straightforward, low-cost solution with immediate benefits but limited scalability.

Water Recycling: This is the most promising solution identified and involves reusing final treated wastewater from the Jaywick Sewage Treatment Works (STW). Currently, the STW discharges about 7.5 million m³ of treated wastewater into the sea annually. If the farms in this study could utilise even just 50% of this resource, it could provide a significant water supply, meeting all modelled future demand scenarios. SWS proposed a system whereby the water would be treated using constructed wetlands and reservoir storage.

On-Farm Storage Reservoirs with High Flow Abstraction: While reservoirs are a proven method for securing irrigation water in this case, their potential is limited due to a lack of available winter water for licensing, as local surface water catchments don’t have enough surplus even if high flow periods are considered according to the LRO report by SWS. As a result, reservoirs alone are not a viable solution unless additional winter abstraction sources are made available or paired with options that increase water availability, such as water recycling. As a standalone solution, this option could provide up to 50,000m³ of additional water.

Water Sharing Agreements: SWS explored agreements that would enable the physical transfer of water between farms and reservoirs via a pipeline network. However, the study found that without additional water supply from recycling, water sharing alone would not significantly enhance resilience. Farmers already rotate crops to optimise water use, and existing land rental agreements facilitate sharing, leaving limited opportunities for further resource gains.

Advance Water Recycling: The report recommends progressing with the Water Recycling LRO to support sustainable water management.

Model for Sustainability: If successful, a water recycling project could serve as a model for sustainable water management, benefiting both farmers and the wider environment.

Essential Next Steps: A full feasibility study on water recycling, engagement with the Environment Agency on regulatory requirements, and identification of funding opportunities are crucial.

Collaborative Approach: This study highlights the importance of early stakeholder collaboration and integrating multiple solutions to build a resilient, sustainable agricultural water supply system.

Water Deficit: The River Lark catchment faces significant water deficit risks due to climate change, with farmers needing to address a projected 4,000,000m³ shortfall by 2050 under the worst-case (driest) scenario.

Collaborative Solutions: The farm group, already part of a WAG, is focusing on collaborative, long-term solutions such as water storage expansion, water sharing agreements, and a demand reduction discussion group to optimise resources.

Demand Reduction: Although it is uncommon for farmers to collaborate on demand-side LROs, this farm group could achieve a 15% reduction in water demand by working together.

Exploring Further LROs: Ricardo recommends that the farm group explore additional water sources, such as drainage water and rainwater harvesting, as alternatives to mitigate water deficits during extreme dry years.

Wetland Water Requirements: The Ouse Washes Landscape Recovery project has commissioned Water Mass Balance studies to determine the water requirements and associated funding for wetland creation and management. Until the results of these studies are known, the viability of these LROs remains uncertain.

Ample Winter Water Availability: Significant water is available in winter when drainage water is pumped from ditches into rivers. Storing this water in ditches or reservoirs could provide a reliable supply for wetland creation.

Integrating Flood Management and Water Resources: Expanding IDB pump capacity could enable wetland creation while improving flood resilience, ensuring water can be removed when needed. This multi-benefit approach would support climate resilience and biodiversity.

Next Steps: Farmers should assess their water needs and conduct cost-benefit analyses once clearer financial incentives emerge, through Ouse Washes Landscape Recovery, other Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes, grants, or private investment.

Pilot Study in the Thet: LRO Case Study 1

Pilot Screening Study in the Thet Catchment

Overview

In the Thet Catchment of East Anglia, 45 kilometres southwest of Norwich, two farms facing significant water challenges became the first to participate in a Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study. Commissioned by the Environment Agency with funding from the Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government, and conducted by JBA Consulting, the pilot LRO study explored practical, collaborative solutions to improve water resilience amid fluctuating availability and tightening regulatory constraints.

Growing Water Challenges in the Thet

Surface water for new licences in the Thet Catchment is available only about 20% of the time, highlighting the area's unreliable water resources. In 2018, the farms in this study experienced a 25% reduction in their time-limited annual abstraction licence volumes, with further regulatory reductions expected. This makes it difficult to meet irrigation demands, particularly during droughts, which negatively impacts crop yields.

Climate change intensifies these challenges, bringing hotter, drier summers, wetter winters, and increased downstream flooding. Competition for water from public water supply and environmental needs further limits agricultural access. Both farms report using 95-100% of their licensed water volumes in recent dry years, increasing the urgency to secure sustainable water sources.

"The farmers' collaborative spirit is crucial for the success and sustainability of these initiatives, which aim to address the complexities of water resource management in a holistic manner."

- The Thet Catchment LRO Screening Study Report

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

To address these challenges, JBA used their established LRO screening and ranking methodology to assess 17 potential options, evaluating water yield, cost, and environmental impact. In collaboration with the farms, they refined criteria and identified practical solutions, considering the farms' strong interest in working together and exploring innovative water management strategies. This process led to three top-ranked options:

Benefits and Challenges of Implementing LROs

Long-Term Gains from Water Storage and Sharing

Despite significant upfront and ongoing infrastructure costs (e.g., reservoirs, pipelines), the study confirms that investing in larger reservoirs and high-flow abstraction is justified by long-term gains in water availability and crop yield stability. These strategies ensure a reliable water supply during dry years and low inflow periods. The study also suggests that there could be benefits associated with managing small floods if high-flow water is diverted to irrigation reservoirs.

Water sharing offers a flexible, cost-effective alternative to traditional infrastructure with the potential for quick implementation, making it especially valuable in areas with financial constraints. This approach also has room for growth, with broader, catchment-scale initiatives having the potential to significantly improve water security and resilience.

Together, these strategies enhance agricultural productivity, reduce financial risks, and provide resilience against climate change and regulatory pressures. For the farms in this study, implementing a 600,000 m³ reservoir and increasing water availability by 5% through water sharing would provide an additional 658,515 m³ of water, with an estimated economic value of £2.68 million*.

Practical Challenges to Consider

Notable barriers include regulatory challenges, such as the fixed nature of water abstraction licensing, the planning approval processes for infrastructure projects, and the financial cost of larger investments. Additionally, current licensing rules for surface water lack the flexibility needed for high-flow abstraction, limiting farms’ ability to fully utilise excess water.

Farmers in the study also reported that Area Environment Agency staff have expressed concerns that water-sharing agreements could lead to increased abstraction above baseline levels, potentially resulting in deteriorating river flows and ecology. While water trading and sharing present promising opportunities, they require cooperation among more stakeholders and greater regulatory flexibility.

💡Key Takeaways

* Assumption based on the value of £3.30 per m3/d of water used for irrigation in a dry year in 2020 (irrigation-strategy-2020.pdf (ukia.org)), which has been adjusted for inflation to 2024 to £4.07 per m3/d (Inflation calculator | Bank of England)

Horticulture near Chichester: LRO Case Study 2

Horticulture near Chichester

Glasshouses growing strawberries in one of the horticultural operations featured in the study. Photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo.

Glasshouses growing strawberries in one of the horticultural operations featured in the study. Photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo. Overview

The Chichester Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study focuses on three horticultural businesses operating between Chichester and Bognor Regis, West Sussex. Together, these businesses manage 950 hectares of irrigated land, including glasshouses, polytunnels, and open fields producing a range of berries, ornamental flowers, trees, and vegetables. With their operations heavily reliant on water, these growers are increasingly concerned about future abstraction pressures, climate change, and the need for operational expansion. To address these challenges, the group participated in an LRO screening study commissioned by the Environment Agency, funded by Defra, and conducted by Ricardo.

Existing Water Management Techniques

Water demand for agriculture and horticulture in southeast England is projected to rise steadily during the 21st century, with horticulture requiring the highest volume, followed by spray irrigation. The three businesses involved in this study have already made significant investments in water resilience, including reservoirs (with planned expansions), rainwater harvesting infrastructure, and demand-reduction measures such as precision irrigation, soil moisture monitoring, and leakage control.

Despite these efforts, water demand is near the maximum licensed allocation, and climate change is expected to further reduce supply. Key challenges include insufficient storage capacity, regulatory uncertainties around abstraction licences, projected water deficits, and limited groundwater use due to high salinity near the coast. Forecasting by Ricardo indicates that all three growers will face shortages by 2050 without additional interventions.

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

Using the LRO Screening Methodology, Ricardo assessed potential LROs, prioritising cost, reliability, and longevity based on conversations with the grower group. Given their existing advanced water management systems, including reservoirs, rainwater harvesting, and precision irrigation, many LROs were ruled out as they were already in use at varying scales. The top three solutions were identified as follows:

1. Rainwater Harvesting and Water Storage Reservoirs: Due to limited storage capacity, a significant amount of rainwater collected from existing roofs is lost as overflow rather than being fully utilised. Ricardo found that optimising storage, through new reservoirs, deepening existing ones, shared reservoir capacity, or additional storage tanks, could provide an additional 160,000 m³ of water from currently unused rainwater.

2. High Flow Water Use: Several areas across the three sites are at risk of flooding from nearby streams, which are located close to existing and planned reservoirs. This LRO explores the potential to use high-flow water to replenish reservoirs, either through controlled abstraction during peak flows or by capturing floodwaters that breach riverbanks. If implemented, this approach could require expanding reservoir capacity by up to 193,000 m³, considering the surplus water that would become available.

3. Water Sharing: This approach combines physical water transfers and water rights sharing agreements to optimise resource use. Rainwater, floodwater, and licensed surface water would be distributed through a shared reservoir and piping network, while Water Rights Sharing Agreements would allow growers to aggregate groundwater licences, maximising headroom and flexibility. If implemented, up to 265,000 m³ of currently unused water in the form of rainwater overflow and abstraction headroom could be shared in the driest years, enhancing overall water resilience.

Benefits

Benefits

Glasshouses at one of the horticulture operations featured in the study. Photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo. Maximising rainwater harvesting, expanding storage, and utilising high-flow water and water sharing would significantly enhance water resilience for the three horticultural businesses. These solutions improve drought preparedness, reduce reliance on abstraction, and optimise water distribution across sites. These solutions offer a collaborative approach to securing long-term water availability for horticultural production.

Glasshouses at one of the horticulture operations featured in the study. Photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo. Maximising rainwater harvesting, expanding storage, and utilising high-flow water and water sharing would significantly enhance water resilience for the three horticultural businesses. These solutions improve drought preparedness, reduce reliance on abstraction, and optimise water distribution across sites. These solutions offer a collaborative approach to securing long-term water availability for horticultural production.

Potential Challenges

While the proposed solutions are promising, several challenges remain. Uncertainty over future abstraction licences, particularly for high flow and floodwater capture, persists until licence applications are determined. Securing planning permissions for new or expanded reservoirs may also be difficult due to potential concerns from local authorities about environmental impact and land use. Additionally, coordinating water sharing with landowners outside this study could be complex and require facilitation. The high cost of reservoirs and a pipeline infrastructure pose further challenges. Early engagement with stakeholders, including the Environment Agency and local councils, is crucial to address these concerns and ensure smooth approval. Without regulatory support, the projects risk delays or restrictions, limiting its impact.

💡Key Takeaways

🔍 In Focus: Rainwater Harvesting in England

Rainwater harvesting is the process of collecting, storing, and using rainwater that runs off rooftops, greenhouses, or other surfaces. In agriculture, it is commonly used to supplement irrigation, reduce reliance on mains or abstracted water, and improve water security. Unlike groundwater or surface water abstraction, rainwater harvesting typically does not require an abstraction licence from the Environment Agency, provided the water is collected before reaching natural watercourses and does not alter normal flow. However, a licence may be required if harvested rainwater is combined with groundwater or surface water for abstraction or transfer. For detailed guidance, refer to the Environment Agency’s Rainwater Harvesting Regulatory Position Statement.

Collaboration Along the River Roding: LRO Case Study 3

Collaboration Along the River Roding

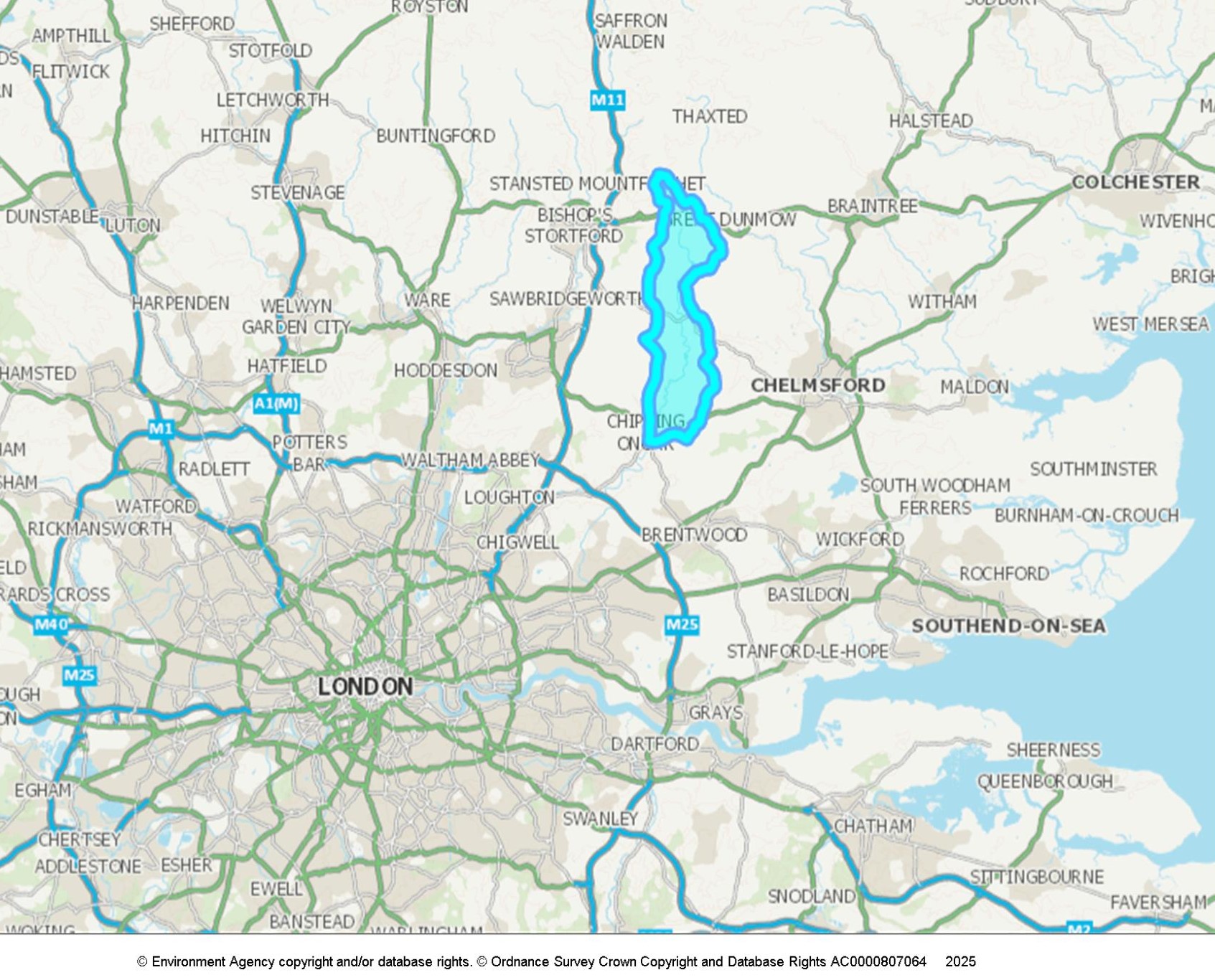

Overview

The Roding Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study explores water resilience solutions for four agricultural businesses dispersed along the River Roding, 30 km northeast of London. Commissioned by the Environment Agency, funded by Defra, and conducted by JBA Consulting, the study builds on the farmers’ existing collaboration within a grower’s association to develop innovative strategies for managing fluctuating water availability and regulatory constraints to strengthen long-term water security.

Growing Water Challenges Along the River Roding

The Upper Roding catchment experiences significant seasonal variability, with high winter flows followed by dry summers, making consistent irrigation difficult. In the winter, frequent and severe flooding, typically one to two out-of-bank events per year, damages agricultural infrastructure and reduces land productivity. Urban developments, including Stansted Airport and housing projects, have increased runoff, further exacerbating these issues.

In dry summer months, existing reservoirs and abstraction capacities have supplied sufficient water. One farm, despite operating five reservoirs, still struggles to meet demand, while another relies on rented reservoirs, leaving it vulnerable to changing agreements or restricted access. Abstraction licensing further complicates water management, limiting opportunities for new abstraction and making it difficult for farmers to fill existing reservoirs. These challenges highlight the need for innovative, long-term solutions.

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

With the farms spread across multiple sub-catchments along the River Roding, some up to 24 km apart, certain LROs were constrained by what could realistically be implemented as a group. Despite this, stakeholder engagement revealed strong support for innovative, collaborative strategies, particularly those centred on shared resources and floodwater management.

Benefits

This study identified significant volumes of winter water that could be captured to support irrigation needs. Restricting abstraction to high-flow months (November–March) minimises downstream impacts during dry summer growing seasons, ensuring irrigation needs are met without compromising environmental flows. Additionally, high-flow abstraction can potentially help mitigate local flooding while increasing water storage. Designing reservoirs to provide resilience for a full irrigation season, 100,000 m³ in this case, ensures storage infrastructure remains both feasible and beneficial for stakeholders and the environment.

This study identified significant volumes of winter water that could be captured to support irrigation needs. Restricting abstraction to high-flow months (November–March) minimises downstream impacts during dry summer growing seasons, ensuring irrigation needs are met without compromising environmental flows. Additionally, high-flow abstraction can potentially help mitigate local flooding while increasing water storage. Designing reservoirs to provide resilience for a full irrigation season, 100,000 m³ in this case, ensures storage infrastructure remains both feasible and beneficial for stakeholders and the environment.

The underutilised abstraction licences in the Upper Roding catchment present an opportunity for collaborative agreements, reducing reliance on new abstractions (where water availability is low) while promoting equitable water access. Water sharing offers a cost-effective and scalable solution for farms facing financial or regulatory barriers to securing additional water resources.

Barriers to Consider

While farm storage reservoirs offer long-term reliability, they require high upfront investment, with a 100,000 m³ clay-built reservoir estimated at £180,000 for initial building costs. Additionally, current abstraction licensing policy, particularly for high-flow abstractions, limits farmers' ability to fully utilise available winter water. Additionally, there is a risk that the floodwater coming from Stansted Airport may not be of good enough quality for agriculture.

Modifying or aggregating licences would also require regulatory approval and negotiations to ensure compliance with water management policies. Water sharing and trading are constrained by current regulations, with limited options to aggregate or transfer licences for optimised use. Although water sharing is a cost-effective solution, it still requires infrastructure investment, including pipelines, pumps, and monitoring systems. Successful implementation depends on collaboration among farmers, including those downstream with underutilised licences, to enhance resilience and resource efficiency.

💡Key Takeaways

A Whole-Catchment Approach in the Nar: LRO Case Study 4

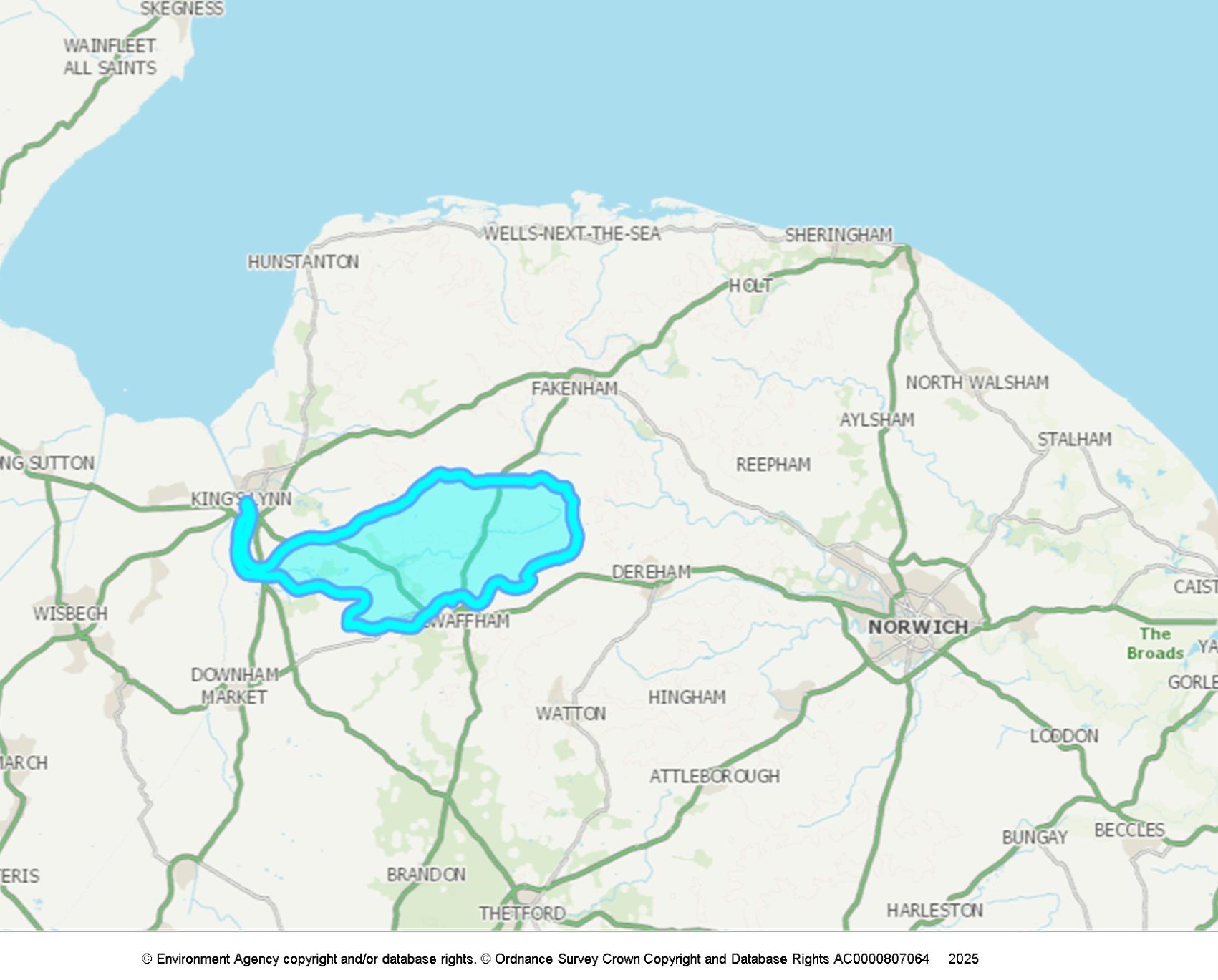

A Whole-Catchment Approach in the Nar  Overview

Overview

In the Nar Catchment of East Anglia, near King’s Lynn, four farms spanning 5,000 hectares participated in a Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study, commissioned by the Environment Agency and funded by Defra. The study aimed to enhance water resource resilience to support the farms' commercial agricultural activities. Led by consultants at Brown & Co, it explored four distinct LRO proposals, emphasising a whole-catchment approach and demonstrating the diverse options available to farms working collaboratively at this scale.

Water and Financial Pressures in the Nar

For the four farms, financial pressures have increased due to the transition from the Basic Payment Scheme to the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), reducing their overall cash flow. To offset this, they participate in a Landscape Recovery project, which promotes large-scale, collaborative environmental initiatives, particularly around the River Nar, a globally rare chalk stream.

Irrigation is critical for sustaining high yields and profitability, especially given the farms’ susceptibility to water shortages. They currently rely on three surface water storage winter abstraction licences from the River Nar, which feed into three reservoirs. Water is then distributed across the farms through an extensive piping system. One farm also has a semi-formal water transfer agreement to import water from other licence holders in the catchment.

Farmers expressed concern over several key threats to their businesses, including the potential reduction and/or loss of irrigation licences, climate change, the removal of area-based subsidies, the uncertainty of environmental payments, fluctuating global commodity markets, and rising production costs.

🧩 Four Possible Solutions

To address these challenges, Brown & Co. used the LRO screening methodology to evaluate options, with the farm group favouring long-term solutions that aligned with existing initiatives like the Landscape Recovery Project.

💡Key Takeaways: 4 Diverse Options

The Nar screening study evaluated four distinct LRO options, each offering different trade-offs in feasibility, cost, and impact.

Ultimately, a combination of these strategies, such as leveraging automation for efficiency while pursuing outflow collection for increased supply, may offer the most resilient and sustainable water management approach for the catchment. Effective catchment-wide cooperation will be crucial, requiring commitment from farmers, regulators, and stakeholders to develop long-term, scalable water management strategies that benefit both agriculture and the environment.

🔍In Focus: What is Managed Aquifer Recharge?

Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) is a water management technique that involves artificially recharging underground aquifers with surface water or treated wastewater. This process helps replenish groundwater supplies, especially in regions facing water scarcity in England. MAR can be done through methods such as infiltration basins, wells, or injection systems, and it improves water storage, increases drought resilience, and can also improve water quality by filtering it through natural soil layers.

Water Recycling in Weeley Heath: LRO Case Study 5

Water Recycling in Weeley Heath

Overview

The Weeley Heath Local Resource Option (LRO) Screening Study, commissioned by the Environment Agency, funded by Defra, and conducted by Sustainable Water Solutions (SWS), explores water resource solutions for six farmers in Weeley Heath, Essex. As one of the UK’s driest regions, the Tendring Peninsula faces growing pressure on water resources due to increasing agricultural demand, climate change, and environmental regulations. The study identified practical, cost-effective, and collaborative strategies to enhance long-term water security.

Water Challenges in the Tendring Peninsula

With an annual average rainfall of just 563mm, the Tendring Peninsula’s large agricultural sector relies heavily on irrigation, particularly for high-value products like onions, turf, and potatoes. Farmers here mostly depend on small streams, but climate projections indicate a 15% decline in summer rainfall by 2030, reducing available surface water, especially during peak irrigation periods. SWS estimates that maintaining current irrigation levels would require an additional 181,000 m³ of water per year, rising to 1,153,000 m³ to maximise land use and support expansion. Meanwhile, regulatory changes under the Water Framework Directive and the Environment Act 2021 will drive reviews of environmental sustainability, which may lead to changes in abstraction licensing and impact access to water supplies.

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

Using the LRO Screening Methodology, SWS evaluated potential LROs, considering criteria such as water security, economic feasibility, environmental impact, and regulatory acceptability. Following extensive stakeholder consultations, three primary options emerged as the most viable:

Benefits of Water Recycling, an Innovative Solution

The study highlights the potential of water recycling to transform agricultural water management in England. Water recycling offers a unique opportunity for agriculture to reuse effluent, providing a scalable solution for drought-prone regions. While it requires regulatory support and investment, this approach could offer a reliable and predictable water source while easing pressure on groundwater and surface water. Additionally, it could reduce discharges into marine ecosystems and promote nutrient recycling, offering valuable environmental benefits.

By using recycled water, which is typically treated to remove excess nutrients, farmers can achieve nutrient neutrality. This means their farming activities wouldn’t contribute to an increase in harmful nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen in nearby ecosystems. As a result, farmers could potentially earn ‘nutrient credits’, which are certificates that recognise their efforts to reduce phosphate pollution. These credits can then be sold to others who need to offset their environmental impact, providing a financial incentive for more sustainable farming practices.

Potential Barriers to Implementation

The use of water recycling across England is limited and would likely require regulatory approval from the Environment Agency, with STW discharge volumes potentially limited due to environmental flow requirements for tide and estuary systems. Negative public perception of water recycling, along with health and safety concerns regarding the potential presence of pathogens or hazardous substances, could pose additional challenges. There is also uncertainty around commitments to supply wastewater from STW and the potential for unregulated costs from the water company. Estimated costs for treatment and distribution infrastructure range from £580,000 to £1,040,000, requiring further feasibility assessments and funding support. Over 10–12 years, the scheme's operational and loan repayment costs are expected to result in a price of 25p–35p/m³.

💡Key Takeaways

🔍In Focus: What is Water Recycling?

Water recycling involves repurposing treated wastewater from sewage treatment works (STWs) for non-potable uses, such as agricultural irrigation. After undergoing multiple treatment processes, the water is purified to meet environmental and safety standards before being discharged, often into rivers or the sea. By capturing and reusing this water instead, farmers can access a reliable, drought-resistant supply, reducing pressure on freshwater resources and improving water security in agriculture.

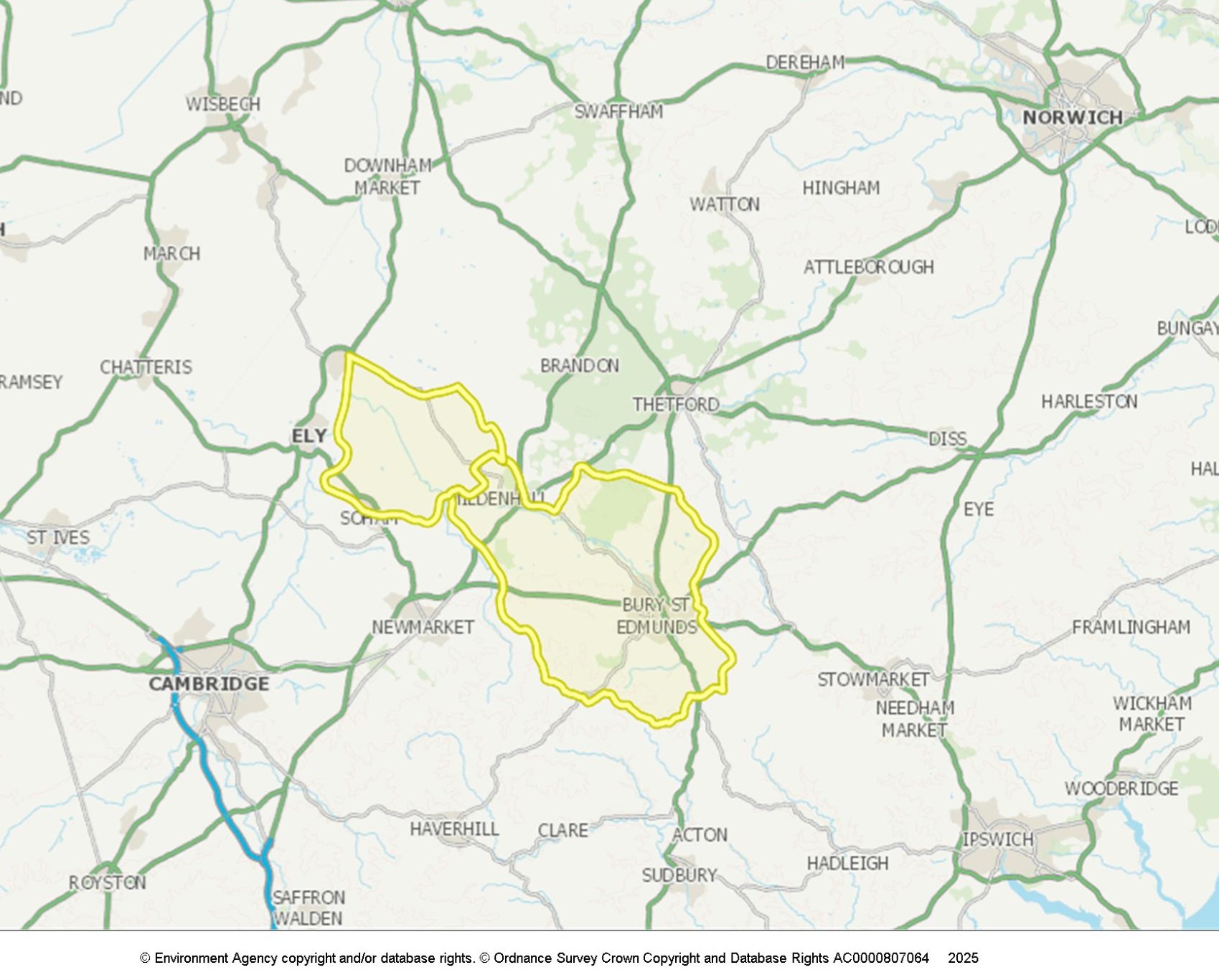

Collaboration in the Lark: LRO Case Study 6

Collaboration in the Lark

Overview

The Lark Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study examined eight agricultural businesses in Suffolk's River Lark catchment, which collectively manage 10,000 hectares of irrigated crops, including root vegetables, cereals, maize, and some glasshouse and amenity horticulture. These farms collaborate through a Water Abstractor Group (WAG) and share growing concerns about future water deficits due to climate change and potential abstraction licence reforms. To explore strategies for enhancing water resilience, they participated in an LRO screening study commissioned by the Environment Agency, funded by Defra, and conducted by Ricardo.

Water Challenges in the River Lark

Eastern England is the UK’s driest region, receiving only two-thirds of the national average rainfall and classified as severely water stressed by the Environment Agency. With warmer, drier, and longer growing seasons, demand for spray and drip irrigation in the region is expected to more than double by 2050.

Despite investments in water resources, including eight existing reservoirs and planned expansions, the farm group anticipates future water shortages due to climate change and potential abstraction licence reforms. Currently, they rely on licensed groundwater and surface water from the River Lark and its tributaries. Supply and demand forecasting by Ricardo, conducted as part of the screening study, found that under the driest climate change scenario, the group would face a 4,000,000m³ water deficit by 2050. To address this, the farms must secure additional water sources and improve water use efficiency.

⭐Top-Ranked Solutions

To address these concerns, Ricardo applied the LRO screening and ranking methodology to assess potential options, further evaluating the top three based on water yield, cost, and environmental impact. The farm group demonstrated the most interest in LROs that provided collaborative, long-term solutions.

1. Farm Storage Reservoir and High Flow Water Use: To secure water availability in the driest years, additional storage is needed to capture winter surface water abstractions for summer irrigation. Eliminating the projected 2050 water deficit requires 3,500,000 m³ of storage expansion. High-flow abstractions could supply up to 2,600,000 m³ annually in extreme dry years, replenishing existing and new reservoirs for a more resilient supply. If abstraction occurs during 50% of high-flow events, it could yield approximately 729,450 m³ of water.

2. Water Sharing Agreements could help farmers maximise existing licence headroom and high-flow water by sharing stored or abstracted water. This could involve physically transferring water via pipework or the river, or pooling licences through Water Rights Sharing Agreements to allocate water where it is needed most. Ricardo estimated that water sharing could provide 293,000m³ initially, though this is expected to decline to 74,000m³ by 2050. While this approach improves water distribution and reduces individual farm deficits, it is insufficient to fully offset the total water supply deficit.

3. Demand Reduction Techniques: A range of techniques can help reduce water demand, including soil moisture monitoring, water-efficient technologies, improved irrigation methods, leakage control, micro-irrigation, and agroecological farming practices. While farmers typically adopt these independently, the farm group aims to collaborate by forming a discussion group with each other and other catchment users to share best practices and explore expert guidance on implementation. Ricardo estimated that a 15% reduction in demand is achievable through these measures, which could reduce water use by a total of 390,000m³ by 2050.

Considerations

An on-farm storage reservoir within the Lark screening study group, photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo.

An on-farm storage reservoir within the Lark screening study group, photo taken by the consultants at Ricardo.

The River Lark experiences high flows and flooding from autumn to spring, presenting an opportunity to store excess water and reduce summer abstraction demand. However, licence changes would be required to allow high flow abstraction, subject to approval from the Environment Agency to ensure minimal impact on river function and wetland habitats. Under current licensing strategies, only winter abstraction is likely to be permitted for reservoir storage.

Water sharing agreements allow farmers to collaborate on resource management, improving resilience and sustainability. However, many existing licences would need amendments to permit sharing, requiring a review of the licences. Additionally, effective governance would be essential to ensure fair water allocation. While some farmers fully use their licences, others use less, creating potential pressure in dry years for lower-usage farms to share water. The existing WAG may help facilitate agreements.

While demand reduction techniques can lower irrigation needs and minimise water waste, Ricardo recommends exploring additional supply-side LROs, such as drainage water and rainwater harvesting, to mitigate water deficits in extreme dry years. Investment requirements for LRO implementation are significant. Reservoir expansion costs are estimated at £12M–£25M by 2050, pipework for water sharing could total £740,000, and soil moisture monitoring units cost approximately £1,000 each.

💡Key Takeaways:

Developing Wetland near Downham Market: LRO Case Study 7

Developing Wetland near Downham Market

Wet grassland that had already been created by the farm group, photo taken by JBA Consulting.

Wet grassland that had already been created by the farm group, photo taken by JBA Consulting.

Overview

In Norfolk and Cambridgeshire, between Downham Market and Ely, seven farms spanning 500 hectares participated in a Local Resource Option (LRO) Screening Study, commissioned by the Environment Agency and funded by the Ministry for Housing, Communities, and Local Government. The farms are engaged in arable farming, livestock farming, and wetland management, with one farm also participating in a paludiculture trial led by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH). As part of the Ouse Washes Landscape Recovery Project managed by the Royal Society of the Protection of Birds, the group aims to develop wet grassland and other wetland habitats. The screening study, conducted by JBA Consulting, assessed the feasibility, costs, and potential for developing and maintaining wetlands for biodiversity benefits, reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and enhanced water security.

Local Water Challenges

The farms in this study rely heavily on irrigation, using surface water abstraction licences. Most fall within the Cam and Ely Ouse catchment, where water is either unavailable for new licences or only accessible at higher winter flows. Variable weather conditions further impact water availability and crop yields, while growing agricultural demand and the need to maintain surface and groundwater quality add complexity to water management.

Although wetland water requirements are still being researched, the Ouse Washes Landscape Recovery Project estimates that creating and maintaining wet grassland could require approximately 2,000 m³/ha/year between April and June. For the seven farms involved, this amounts to a total water demand of 1,826,000 m³ per year. Considering the group's water demand, existing licences, and one reservoir, JBA estimates that, depending on how much licensed abstraction is allocated to wetland management, six out of the seven farms would experience shortages in a dry year. This issue would worsen with any regulatory summer licence reductions. This highlights the need for new water solutions, as reliable water resources are essential for sustaining wetlands.

The farms are within the jurisdiction of multiple Internal Drainage Boards (IDBs), which regulate water levels for agriculture and the environment by pumping winter water into rivers from the lower lying Fenlands drainage systems, requiring coordination with these authorities. Additionally, the presence of environmentally protected sites requires careful water management to prevent negative impacts on local ecosystems and waterways.

⭐Top Ranked Local Resource Options

After discussions with the farm group and stakeholders, and using the LRO Screening Methodology, JBA identified 14 potential LROs. The farmers’ primary goal was to secure reliable water resources for creating and maintaining wetland habitats. Based on economic viability, supply security, and environmental considerations, the following three options emerged as the top options:

A lode (also known as a drain or water course) on one of the farms in the study. Photo taken by JBA Consulting.

A lode (also known as a drain or water course) on one of the farms in the study. Photo taken by JBA Consulting.

1. Farm Storage Reservoirs: The study found that a 163,000 m³ reservoir could meet the water needs of two of the farms in at least 90% of years. Ample water is available during high-flow winter months, typically pumped from drains and ditches into rivers as drainage water. Capturing and storing some of this water in reservoirs would provide a reliable supply for wetland creation. Water balance analysis confirmed that these reservoirs could be consistently filled each year through a combination of high-flow abstraction, drainage water use, and water sharing or trading.

2. Water Sharing and Water Rights Trading: The group identified several opportunities for water sharing, including sharing licensed abstraction quantities from farm ditches and a potential shared reservoir. Water could be transferred between farms via drainage ditches or a watercourse for re-abstraction. Stakeholders expressed strong support for collaborative water management, recognising it as a cost-effective, scalable solution for areas with financial or regulatory constraints.

3. Drainage Water Use: Discussions with farmers and the Ely area IDB revealed strong support for maintaining higher water tables, as this would benefit both agriculture and wetland creation. Currently, IDBs avoid higher water tables due to the potential for increased flood risk with existing assets. However, if IDB pumps were upgraded to larger capacity speed pumps, it could enable wetland creation and improve flood resilience, knowing that water could be pumped away when needed.

Challenges / Considerations

While the proposed solutions offer promising avenues for improving water security and wetland creation, several challenges must be considered. Farm storage reservoirs require high upfront costs, and in this context their pumps must withstand sediment-heavy water, increasing maintenance demands. Raising water levels, a key factor for wetland development, could heighten flood risks and currently IDBs lack the funding to upgrade pumps to support both flood resilience and wetland creation using drainage water. Existing licensing frameworks, based on seasons rather than real-time water levels, make it difficult to take advantage of high winters flows. While water sharing and water rights trading is a low-cost scalable option, successful water sharing would require regulatory approval, infrastructure investment, and careful operational coordination to ensure compliance and efficiency.

💡Key Takeaways

🔍In Focus: Paludiculture, Wetland Restoration, and IDBs

Paludiculture: A form of sustainable agriculture that cultivates crops such as celery and cranberry as well as reeds on wet or rewetted peatlands. It supports biodiversity, reduces carbon emissions, and maintains water storage while allowing productive land use.

Wetland Restoration: The process of returning degraded wetlands to their natural state by reintroducing water, restoring vegetation, and improving habitat conditions to support wildlife and ecosystem functions.

Water Sharing to Boost Resilience: LRO Case Study 8

Water Sharing to Boost Resilience

Context and Challenges

One Local Resource Option (LRO) screening study examined a group of three farming & horticultural businesses managing around 1000 hectares of irrigated land, including glasshouses, polytunnels and open fields, growing a variety of soft fruit, vegetables and cut flowers. Water is of vital importance to these operations, and whilst the growers have plans for business growth, they also face the challenges of tightening abstraction conditions and a changing climate. To explore practical ways to strengthen resilience, the group took part in a consultant-led LRO screening study, commissioned by the Environment Agency and funded by Defra.

A core line of enquiry was water sharing: physically transferring stored water between neighbouring sites and, where appropriate, sharing or aggregating water abstraction rights on paper to make better use of winter rainwater and licence headroom. In dry years, one site can be short just as a neighbour is spilling rainwater or carrying unused capacity; the study asked whether a structured sharing arrangement could turn those mismatches into more reliable summer supply while remaining within licence and environmental safeguards.

Water Sharing in Practice

At the heart of water sharing is headroom - the recoverable and transferable water a business can make available without compromising its own reliability, once you account for licence rules (e.g. abstraction rates, volumes, Hands-off Flow and seasons), pump/pipe limits, timing, and available storage. In practice, access to water through headroom comes from (i) winter rainwater that would otherwise overflow (but only if it can be moved or stored in time), (ii) unused licensed volume or rate that can be abstracted and banked lawfully, and (iii) spare storage space that can receive transfers. The study used simple monthly balances (demand, inflows, licensed abstraction, storage) to identify usable headroom and where neighbouring deficits occur.

On that basis, the three businesses together had an additional pool of 265,000 m³ in dry years, made up of roughly 160,000 m³ of rainwater that currently overflows plus 105,000 m³ of recoverable licence headroom. For scale, the group’s average-year water use is about 2.42 million m³ per year, so the recoverable pool equates to roughly 11% of typical annual use. In years when winter high-flow opportunities are also captured, the existing or planned reservoirs could accommodate a further ~193,000 m³, subject to the same storage and transfer constraints.

A Worked Example

To illustrate how this plays out on the ground, consider a representative dry year. Farm B faces a summer supply gap of roughly 140,000 m³. Farm A has winter rainwater harvesting system that fills early and then spills; Farm C has some licence headroom and spare storage in the spring (April to May). With a short transfer main and pumps, 100,000 m³ can move from A to B in late spring, and 40,000 m³ from C to B during a July dry spell. A simple monthly storage check confirms there is room to hold those transfers until they are needed. The result is fewer crop-stress days for B, while A and C retain buffers for their own operations. Crucially, more of the summer use is supplied from stored winter water, easing pressure on low flows due to reduced abstraction in summer months.

Making It Work: Engineering, rules and consents

Making sharing work requires practical links and clear rules. The engineering is modest: short pipelines between the nearest reservoirs sized for realistic duties (for example, 100–300 m³/h), with meters and basic telemetry so everyone can see what moved, when and at what energy cost. The governance is what keeps it fair: a water-sharing agreement (or company) that sets triggers and priorities in dry spells, allocates costs (typically a pence-per-m³ transfer price reflecting energy, maintenance and depreciation), defines data and metering standards, and explains how to scale back if the season tightens. On the regulatory side, early pre-application conversations with the Environment Agency smooth decisions on licence aggregation or trading mechanics and any high-flow triggers.

If natural channels or IDB drains are involved for conveyance, land-drainage consents and legal agreements will be needed; new or expanded storage may also require planning and, in some locations, HRA/EIA screening. For conveyance through natural channels a put and take abstraction licence will be required from the Environment Agency, this may be conditioned with a requirement for a greater volume of water to be discharged than is subsequently re-abstracted to allow for any evapotranspiration or bankside losses and for a delay or ‘lag time’ between discharge and re-abstraction to allow time for the movement of water.

Costs

For the water sharing option, costs fall into three categories:

1. infrastructure to link reservoirs

2. legal/administrative set-up of the sharing arrangements

3. ongoing water management including power for pumping.

As an illustration, installing about 2,930 m of new transfer main between two sites (8-inch pipe) was estimated at £89,000 (pipework £61.5k, ancillaries £5.9k, and land easements £21.7k), excluding any reuse of existing pipework and hydrants. The report notes there is significant existing infrastructure in the area, so actual costs would need confirming after surveys. Indicative legal/administration and water-management costs over ten years were estimated at £100k–£150k, depending on complexity and timelines. If the group opts for a third-party online platform to monitor and manage supplies in real time, allow an additional £30k+ (software and functionality dependent). Options relating to solar pumps could be possible in this scenario where reservoirs are being used to buffer flow.

Benefits and Limitations

The benefits are straightforward. Sharing makes better use of water the group already has, winter rain in storage and licensed capacity that would otherwise go unused, turning it into reliable summer supply. It reduces the need for emergency mains top-ups, cuts the risk of yield losses in prolonged dry spells, and lessens direct abstraction during low-flow periods. The limits are equally clear. Sharing does not create water out of thin air and storage remains the backbone. Success depends on trust, transparent information sharing and prompt operations, and every transfer must remain within licence and environmental safeguards.

Practical Next Steps

For these three businesses, the screening indicated that water sharing could potentially convert around 265,000 m³ of currently under-used water into more reliable summer supply, subject to storage, transfer capacity, licence conditions and agreement between parties. A pragmatic way forward would be to test the idea: agree a short memorandum of understanding, run the three-tab water balance to quantify headroom and deficits, speak to regulators early about licensing/conveyance, and pilot one season with conservative transfer volumes. The costs, benefits and operational fit will vary by site, as such a pilot would help establish whether sharing is workable and proportionate for the group, and what adjustments, if any, are needed.